|

|

Fighting Tommy Riley

By Robert Koehler

A Visualeyes Prods.

presentation in association with Jellyworks, LLC.

(International sales: Turtles Crossing, Los Angeles.)

Produced by Bettina Tendler O'Mara. Executive producers,

Diana Deryez Kessler, Paul Kessler. Co-producers, Randy

Turrow, Diana Deryez Kessler, Wayne Witherspoon.

Directed by Eddie O'Flaherty. Screenplay, J.P. Davis.

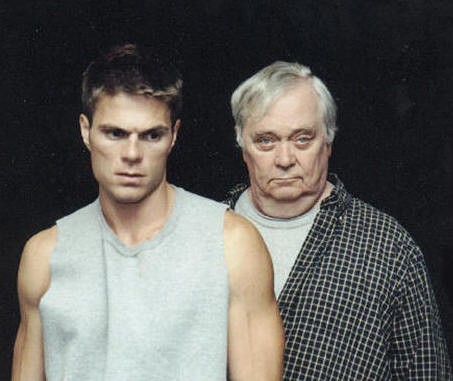

Marty Goldberg - Eddie Jones Tommy Riley - J.P. Davis

Stephanie - Christina Chambers Diane Stone - Diane M.

Tayler Bob Silver - Paul Raci Kane - Don Wallace

In "Fighting Tommy Riley," the winner by a

knockout is Eddie Jones. The vet thesp, regularly

seen in colorful supporting roles, flexes his

considerable muscles as an aging trainer helping revive

the career of a boxer who has lost faith in himself.

Without Jones, pic is a standard drama on the sweet

science with the usual tropes and a slight tweak on the

usual conflicts. With Jones, matchups with fests and

distribs are possible, while the cable arena is a sure

thing.

Tommy (screenwriter

J.P. Davis), all pumped up for his match, mentally

flashes back seven months to the time he and g.f.

Stephanie (Christina Chambers) broke up and when he was

berated in a boxing gym for being too aggressive. But

his low point was witnessed by boxing manager Diane

Stone (Diane M. Tayler) and her partner-trainer Marty

(Jones), who liked what he saw in the kid. At first,

Marty appears to be the stock figure typical in boxing

movies, the older, wiser man who sees greatness where

others see a loser. Marty starts by testing Tommy in a

gym match against a tough sparring partner, while

reminding the short-fused boxer that he needs a bit of

anger management.

In the heart-to-heart scenes

between Marty and Tommy -- so obligatory in the genre

and so often phoned in by actors -- Jones personally

pushes the movie to a higher emotional plane. An actor

who tends not to just inhabit his roles but move right

in and take over the mortgage, Jones appears to

understand Marty's empathy for Tommy at a gut level.

Jones' Marty is several divisions and degrees away from

Burgess Meredith's needling codger in "Rocky," and smart

enough to spot Tommy's habit of faking injuries.

Director Eddie O'Flaherty demonstrates

a flair for widescreen framing, but keeps to a routine

moviemaking style (d.p. Michael Fimognari's vid-lensed

image was undercut by vid projection at the Los Angeles

fest premiere, though a film transfer is promised).

Montages of Tommy's fresh string of victories alternate

with private dramas between him and Marty, and then

Stephanie, who returns to the picture a little too

easily.

A retreat to the woods for training

before a title bout raises the stakes, even as Tommy

gets pressure from powerful, smooth-tongued fight

promoter Bob Silver (Paul Raci) to sign with him and

leave Marty. The old trainer has his own secrets and

desires, which Jones manages to keep so well hidden that

when they burst forth, it has the shock of a jolting

scene in an Arthur Miller play. The film doesn't end in

Milleresque tragedy, though, but with a grown-up sense

of loss.

Davis seems initially too good-looking

to take seriously, but he grows into a role he wrote for

himself, and Tayler does a pro job of playing

counterpoint to whatever Marty has to say. Though it

always feels too staged when the action's outside the

ring, pic has a sweaty background feel that's impressive

for an indie production, and fight scenes play like the

real deal. Print screened contained wall-to-wall temp

tracks from some of Thomas Newman's and Hans Zimmer's

better, moodier scores.

Camera (color,

Panavision widescreen, DV), Michael Fimognari; editor,

Aram Nigoghossian; production designer, Marla Altschuler;

art director, Joe Pew; set decorator, Marsha Daniels;

costume designer, Corenna Gibson; makeup, Hella Hazz;

sound, Eric Rodriguez; supervising sound editor, Joe

Dzuban; associate producer, Don "Kip" Bickel; assistant

director, Bernhard Spoon. July 7, 2004. Reviewed at Los

Angeles Film Festival, June 20, 2004. Copyright � 2004

Reed Business Information. |

|

Fighting Tommy Riley

By Kevin Thomas

Times Staff Writer

Every once in a while a veteran character actor, after a solid

career in films, theater and television, lands a starring role in a

movie that is actually worthy of his talent. With "Fighting Tommy

Riley" it has happened to Eddie Jones, and he brings the experience

of a lifetime in acting to making his character, Marty Goldberg,

unforgettable.

Marty has pretty much given up the

battle of his own bulge, and the portly, white-haired high school

teacher has learned to expect that quotes from Melville, although

spoken by him with the utmost eloquence and understanding, are going

to be lost on his students. Not in the best of health, he is a

solitary man on the threshold of a lonely old age, living in a

book-filled home with his beloved pug. Marty, however, once had

another life, as a promising boxer and later as a trainer. The one

person who seems to care for him is a forceful young woman, Diane

(Diane M. Tayler), a boxing promoter who considers Marty her partner

because he steered her away from a path of self-destruction. Diane

has come across a moody, insecure young fighter named Tommy Riley

(J.P. Davis, who also wrote the film's exceptional script) in whom

she sees potential, and she persuades Marty to become his trainer.

It takes a while for the introverted Tommy to begin to trust Marty,

but once he does he begins to come alive outside the ring as well as

inside it. By the same token it is clear that Marty is in better

spirits than he has been in a very long time, and the month the two

men intend to spend at Marty's mountain cabin, where they will

prepare for Tommy's big match, looks to be an especially happy

period for both of them.

Both Davis' script and Eddie O'Flaherty's direction match Jones'

performance in subtlety. From the first moment Marty appears there

seems to be a shadow hovering over him, and there are signs of an

ingrained, unshakable sadness in him. It's not surprising that in

time Marty should feel love for Tommy or that the boxer begin to

regard Marty as a father figure. There comes a moment of realization

when the nature of Marty's feelings becomes clear, and there is at

this point a shift in focus, from the consideration of the complex

interplay of secrecy and repression within Marty to the

contradictory feelings that sweep over the deeply loyal Tommy. The

boxing sequences in "Fighting Tommy Riley" are intense and

convincing, but as with "Million Dollar Baby" it's what happens

outside the ring that lingers in the heart.

In watching Jones become Marty it's easy to see how Jones won prizes

for his portrayal of Willie Loman in "Death of a Salesman" on stage.

Jones knows how to reach so deep inside himself and is in such

command of his acting skills that Marty's every gesture, look and

movement is expressive and revealing � even when it means to be

concealing.

Davis' Tommy is no less fully realized, and Tayler's Diane

is also well drawn. Christina Chambers is effective as Tommy's

uncomplicated girlfriend, who does not always understand him, which

figures because he's often struggling to understand himself. This

small, lovingly crafted film continually surprises with its depth

and resonance. 'Fighting Tommy Riley' MPAA rating: R for language,

some sexual content Times guidelines: Adult themes and situations

Eddie Jones...Marty Goldberg J.P. Davis...Tommy Riley Diane M.

Tayler...Diane Stone Christina Chambers...Stephanie Bob

Silver...Paul Raci A Freestyle Releasing and Visualeyes Productions

release. Producer-director Eddie O'Flaherty. Producer Bettina

Tendler O'Mara. Executive producers Diana Derycz Kessler and Paul

Kessler. Screenplay by J.P. Davis. Cinematographer Michael Fimognari.

Editor Aram Nigoghossian. Production designer Marla Altschuler. Art

director Joe Pew. Set decorator Marsha Daniels. Running time: 1

hour, 49 minutes. Exclusively at the Regent, 614 No. La Brea Ave.,

L.A., (323) 934-2944. Copyright 2005 Los Angeles Times.

|

|

Fighting Tommy Riley

By Brian Brooks

Hamptons

International Film Festival feature "Fighting Tommy Riley" from

newcomer Eddie O'Flaherty and J.P. Davis has been acquired by the

recently formed Santa Monica distributor Freestyle Releasing, the

company announced over the weekend.

The film, which received the

Kodak Award for Cinematography at the festival, stars J.P. Davis,

who also wrote the screenplay, and actor Eddie Jones, as a boxing

team who must deal with their own personal demons as they struggle

to establish themselves on the fighting circuit.

Susan Jackson, CEO and president of acquisitions at

Freestyle negotiated the deal with Bettina Tendler O' Mara on behalf

of Visualeyes Productions and Jellyworks. Freestyle will handle

North American theatrical distribution, and will release the film in

the second quarter of 2005. Based on Davis' screenplay, the film was

financed and produced by O'Mara's Visualeyes Productions and

Jellyworks, and had its world premiere at the IFP Los Angeles Film

Festival back in June. It screened in competition this weekend in

The Hamptons and CURB Entertainment is handling international sales.

"Eddie O'Flaherty and J.P. Davis have delivered a knock-out feature

film debut of fierce intensity with beautifully realized characters,

exceptionally acted by all, with veteran character actor Eddie Jones

giving a powerful star turning performance which is the tragic

center of the film," commented Freestyle Releasing exec Susan

Jackson in a statement."

The fight scenes are spectacular in their reality and the film is a

great combination of character, action and story." Freestyle

Releasing was formed by Susan Jackson, formerly of Turtles Crossing,

Mark Borde from Innovation Film Group, and Mike Doban from Arcangelo

Entertainment. Their first release is James Redford's "Spin."

|

|

Fighting Tommy Riley

What We Saw At The Hamptons

International Film Festival

A unique

look into the life and relationship between a budding professional

boxer who "almost" made the Olympic Team a few years earlier (played

by JP Davis who also wrote the screenplay) and his trainer played by

Eddie Jones. Director Eddie O'Flaherty takes the audience through

the highs and lows of these two characters and their struggle to

deal with their tortured souls, through the story of a struggling

young boxer who doesn't believe in himself and a worn down trainer

who convinces him that he's got the talent and skill to win.

The dynamic performances and chemistry between

the two actors is remarkable. Veteran actor Eddie Jones grabs your

heart and challenges our place in society.

The boxing scenes are authentically recreated. You will leave

the theater believing that dreams do come true and true friendships

are forever. With other notable performances by Christina Chambers,

Diane M. Tayler, Paul Racci and Don Wallace. �KK

|

|

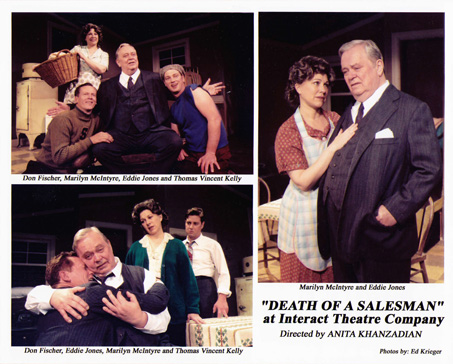

Death of a Salesman

By Dany Margolies

November 08, 2006

This

Arthur Miller classic is relatively foolproof. It's a magic carpet

on which skilled actors can lift audiences to dizzying heights, an

enchanted lantern that lights long-darkened corners of our emotions.

But those who know the script, who have seen the greats perform the

paradigmatic roles, who are familiar with realism and memory plays

and clever amalgams of both, may be disappointed in the staging

here�no reflection on the uniformly superb cast, from principals

through bit players.

Eddie Jones is Willie Loman, acing this mettle-testing iconic part,

wearing with equal parts dignity and shame the heavy mantle of

sadness and fear and irritability.

As Linda, Anne Gee Byrd takes Willie's guff squarely on the chin,

letting us feel the punch instead; Byrd is motherly and worn, but we

can see glimpses of the girl Willie married, and it makes his

transgressions even more pathetic. Aaron McPherson gives Happy more

dimension than is usually seen, his reactions and presence

intensifying every family interaction. Ivan Baccarat's glorious

voice lets us hear Biff's many ages and moods.

Jill Jacobson's The Woman is surprisingly and delightfully

nonvillainous. As Charley, Alan Charof is an acting lesson of his

own, fully immersed in onstage action. Robert Machray is snobby yet

sepulchral as Uncle Ben. Director Bob Collins gets high marks for

his casting (with Coleen Kalbacher). But although each actor is

first-rate, they seem not to have jelled together. They don't occupy

a cohesive world�taking into consideration that some characters are

clearly more of Willie's memory than others. Is the whole a memory

play in Collins' vision? Only if so, then the walls that some

characters see through while others don't are slightly less

troubling. Gelareh Khalioun's costumes seem to borrow from various

periods; again, it works if the play is strictly memory, except that

Biff's present-day style distracts from the character's period

morality. And we can hear the actors gathering backstage for their

curtain calls while Linda is speaking over Willie's grave. Attention

must be paid.

|

|

Death of a Salesman

By Kelly Monaghan

Arthur

Miller's Death of a Salesman enjoys iconic status in the American

theatrical canon and justly so. However, in an odd way, its success

has worked against it. Revivals tend to attract mega-stars to the

role of Willie Loman and the productions built around them tend to

strive for operatic grandeur. The result is often less than

successful, as perfectly illustrated by recent productions starring

Dustin Hoffman and Brian Dennehy. The Willies we get in these

bloated, star-driven vehicles are intriguingly idiosyncratic

(Hoffman) or downright bathetic (Dennehy), but the play inevitably

suffers.

Now Los Angeles' estimable Odyssey Theatre is presenting a

human-scale reading of the play that allows it to speak with the

quiet power that I think Miller intended. The Odyssey production,

under the unobtrusive direction of Bob Collins, allows veteran

character actor Eddie Jones to turn in a masterful performance that

is quite literally heart-wrenching. I have never seen Miller's

merciless deconstruction of the American myth of success rendered

more powerfully or more simply. I confess that I am unfamiliar with

Jones' work, but if this isn't the greatest performance of his

career then I feel cheated from having missed him in earlier roles.

Linda Loman, Willie's long-suffering wife, is often portrayed as a

beaten-down woman in performances that are muted to avoid drawing

attention from the star. Anne Gee Byrd is something a revelation,

giving us a Linda Loman who lives up to Biff's description of her as

a "woman with substance." She is quite simply superb, every inch

Jones' equal and, through her love and loyalty, we are able to see

the Willie that was in the sad, beaten man who is. Ivan Baccarat

(Biff) and Aaron McPherson (Happy) as the Loman's flawed sons do a

good job of making concrete the fatal flaws in the world view Willie

wants so desperately to pass on to them. Baccarat works especially

well with Jones. The scene late in the play in which Biff sees

Willie at his most-human and most-pathetic is embarrassing to watch,

which is just as it should be. Miller, unlike most other

playwrights, has the gift of creating small roles that allow good

actors to score indelible impressions with a few scant moments of

stage time. The supporting performers in this production seize the

opportunity. Robert Machray (Uncle Ben), Alan Charof (Charley),

Jeremy Shouldis (Bernard), and Lou Volpe (Stanley, the waiter) are

all excellent. And Jill Jacobson (The Woman) makes Willie's cruel

betrayal of Linda perfectly understandable.

|

|

Death of a Salesman

By T.S Kerrrigan

American Reporter Theater Critic

May 8,

2002

Los

Angeles -- Arthur Miller's American masterpiece, a penetrating

examination of both what Samuel Johnson called "The Vanity of Human

Wishes" and what Francois Mauriac called "The Desert of Love," is

currently r eceiving

a monumental production at the Interact in North Hollywood under the

inspired direction of Anita Khanzadian. It can be said without

hyperbole that it is one of the best interpretations of this play

that local audiences are likely to see. eceiving

a monumental production at the Interact in North Hollywood under the

inspired direction of Anita Khanzadian. It can be said without

hyperbole that it is one of the best interpretations of this play

that local audiences are likely to see.

Certainly, Eddie Jones is the equal or superior of anyone this

reviewer has seen in the

role of Willie Loman, and that includes Frederic March (from the

film), Lee J. Cobb and Dustin Hoffman (on television), and more

recently Brian Denehy (who Vincent Canby correctly observed was

probably miscast in the role). Jones gives a powerful and complex

portrait of a decent man whose life and career have reached rock

bottom in a world of false values. He gives the full range of

Willie's bluster, anger, weakness and frustration in a manner that

is always convincing. The

contradictions of the character, that have been known to trouble

lesser actors, are dealt with credibly. One cannot readily imagine a

more consummate performance.

Other

standouts in this production include Thomas Vincent Kelly as the

shallow Happy, James Gleason as the pragmatic Charley, the opposite

of Willie in personality and philosophy who nonetheless gives him

the proper epitaph as a man "way out there in the blue, riding on a

smile and a shoeshine." Marilyn McIntyre gives us a different Linda

than we have seen before. The faithful wife of Willie, she has an

ageless quality here. The choices McIntyre makes are never obvious

and essentially effective. In the "attention must be paid" speech

she is completely compelling.

Most of

the smaller roles are also well realized. Kelly Connell makes a

perfect Howard Wagner, Willie's insensitive young boss. Steven Hack

is fine as Bernard, and Bob Larkin fine as Uncle Ben. Don Fischer

seems a little out of his element as Biff in the beginning, but

comes on stronger in the end.

Thomas

Buderwitz's rather bare set is realistic, especially the period

refrigerator which Willie rails against. J. Kent Inasy's lighting is

evocative of the time and mood of the piece, and a definite

improvement over the gloomy darkness seen at the Ahmanson. Paul

Cuneo's original music is also complimentary.

This is

the kind of treatment that Miller's greatest play deserves. It

should under no circumstance be missed by anyone with an interest in

American theater.

|

|

Death of a Salesman

By T.H. McCulloh

Showmag.com

When Noel coward went to see the original

production of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman, producer

Irene Selznick told him it wasn't a play, it was an experience.

Afterward, Coward said to her, "Oh, I wish it had been a play." It

still has problems, even though it has become something of a

classic, but none of the dramaturgical problems can be corrected

until Miller's copyright runs out. Face it, many people today think

Shakespeare's plays have problems, so Miller's in good company.

One of the problems is the central role,

fading salesman Willie Loman. It's one of those roles, like Richard

III and King Lear, that tricks most actors to a size larger than

life and twice as noisy. The original Willie, Lee J. Cobb, blustered

and trumpeted Willie, waved his arms like a windmill and acted it

all over the stage without shame. Brian Dennehy's Willie of a couple

of years ago was a good match for Cobb. On the other hand, one of

Cobb's Broadway replacements, Thomas Mitchell, a much more

technically trained actor, was much deeper and richer, had a great

deal more subtext and was thankfully interior and therefore more

powerful. Like Lear and other similar tragic monuments, Willie is

more effective when the great drama is inside him and not spilling

into the orchestra.

That's the advantage Eddie Jones has as

Willie in this fine production at Interact Theatre in North

Hollywood. His tone and sense of detail is closer to Mitchell, while

still an individual portrait that is painted in rich chiaroscuro,

toned with subtlety and very touching. When Jones does become bigger

than life, there's a valid reason for it other than bowling over the

viewer. His Willie shines with a light deep within Jones'

conception.

On Thomas Buderwitz's simple but very

effective and utilitarian setting, and lit with a fine sense of mood

and shading by J. Kent Inasy, the play is directed by Anita

Khanzadian flawlessly and with a sure connection to Miller's intent.

Marilyn McIntyre's Linda, looking a bit younger for the role, is

nonetheless a rich evocation of a woman living without restraint,

living for her man and her boys, solid in her belief in Willie's

value and desperately concerned for his welfare. It's an enriching

picture of those women who seem to live for home and family but are

strong enough to battle her closest for her husband's survival.

Almost as difficult as Willie are the

characters of his sons, 34-year-old Biff, who's a failure as a man,

as he was a phony success as a teenage sports hero, and younger son

Happy, a sleazy, self-absorbed boob without much concern for his

father's problem as long as he gets laid regularly. Don Fischer is

ultimately touching as Biff as his actual relationship with Willie

unfolds and his own image of self-worth proves pointless. As Happy,

Thomas Vincent Kelly thankfully provides enough likable qualities to

make Happy's sleaze at least acceptable until it overpowers his own

relationship with Willie. The best of Willie's sons to be seen in a

long time.

As successful neighbors Charley and his very

bright son Bernard, a nerd who shines as he leaves his best friend

Biff wallowing in a lack of direction, James Gleason and Steven Hack

are excellent, contained and sure as they should be. Bob Larkin is

interesting as Willie's memory of his older brother Ben, but Ben is

extra baggage which some future director will surely delete, as is

the Boston woman Biff discovers Willie is cavorting with, played

here with fine style and some fire by Amanda Carlin. The whole

company shines in this staging, and special mention should be made

of Andrew Leman's waiter Stanley, a microscopic portrait that

sparkles with humor and honesty.

|

|

A Letter to Eddie

Dear Eddie and Anita,

As I've been reading the obituaries/articles of Arthur

Miller with their in-depth discussions of "Death of a

Salesman," I've been reliving the astonishing production

you brought us. Both in the Interactivity reading and

the full production, we in the audience were knocked

dumb. Yes, it's an extremely powerful play as written,

absolutely brilliant, one of the greatest ever written.

But your staging and interpretation worked special

magic. Being in such close physical proximity certainly

gave it extra power - no safe distance from which to

view; we were eavesdroppers and couldn't escape. By the

end we were holding our breaths, anticipating the

inevitable but still holding out hope for this

misguided, rudderless man. Anita, you found all of the

nooks and crannies, guiding us through it artfully:

clean, spare and poignant, your direction allowed the

enormity of the story to unfold without clutter: with

clarity and power, beautifully calibrated. We knew we

were in good hands from the get-go.

Eddie, I shall never

forget your accomplishment as Willie Loman. You ripped my

heart out, but you did it honestly. You met the man and

the two of you became one. You belong in the pantheon,

next to Lee J. Cobb and the others whom they trumpet in

the articles. At the end, gripping your packet of seeds,

lost and desperate, I wanted to run up on the stage and

save you from yourself. This is no mean accomplishment

as we had seen the Willie who was also capable of

less-than-honorable behavior. Your vulnerability

combined with the last breath of determinism, talking

yourself into believing in what had defined your life

even as it is slipping away... the scene in the office

with Jimmy Gleason, as you are grasping for a shred of

dignity, was so alive and true and painful it was

difficult to watch - and all the rest; how specific and

fully-realized the psychology of this man was in the

moment-to-painful-moment unraveling... to say your

performance was memorable is putting it mildly. I love

you both and thank you for giving me this experience.

|

|

The Dreamer Examines His Pillow

By Dany Margolies

Sept 12, 2007

Backstage.com

When actor Amanda Tepe heads downstairs and into the

first scene, playing opposite Jeffrey Stubblefield

in John Patrick Shanley's examination of

self-examination, it may be your reaction to think,

"Wow, she looks like someone else I've seen on

stage. But who?" The question lingers gently, even

as she and Stubblefield skillfully play Donna and

Tommy, a couple at a spider's web of emotional

crossroads. Perhaps all is a dream? Smarter minds

can better interpret the puzzling script. Donna is,

as the play describes, a tough girl, and Tepe plays

her as a caged panther. Tommy is the consummate

burgeoning artist, whom Stubblefield makes slightly

self-absorbed, slightly oblivious. Stubblefield is

reactive to Tepe's hot-wire volatility; she will not

let him off any hooks.

And then comes

the scene shared by Tepe and Eddie Jones as her dad.

And now we know who she reminds us of. She is a

feminine version of Jones, bearing his square jaw,

pertly upturned nose, and gimlet-gaze eyes. That

director Anita Khanzadian, she's a smart cookie for

casting Tepe against Jones, because the family

resemblance propels our readiness to believe we're

watching a father and daughter. The actors then earn

the rest of our attention by their exquisite

interpretation of that relationship. Khanzadian

seems willing to allow a different Donna to emerge

when with Dad: This one is warmer, subtly softer,

always hoping for his adoration even as she begs him

to help her win Tommy's. Her words are harsh, but

this Donna loves her daddy. Playing the once-wayward

father, Jones doesn't merely "listen" to Donna as

would so many actors as Dad; instead, he may be

occasionally tuning her out, watching the child he

may have so long ignored, perhaps thrilled she's

come for advice, possibly relieved enough to finally

share his own examinations of his own pillow.

It's an honor to watch Jones at work. Victoria

Profitt's set design enhances the play's many art

metaphors: Tommy's hovel is rendered in charcoals,

Dad's in sanguine. But it's the well-shaded set of

performances that keeps us marveling. Presented by

Deep Breath and a Leap Productions and Interact

Theatre Company at the McCadden Place Theatre, 1157

N. McCadden Pl., Hollywood. Thu.-Sat. 8 p.m., Sun. 2

p.m. Sep. 7-Oct. 14. (818) 765-8732

www.plays411.com/dreamer.

|

|

The Dreamer Examines His Pillow

By Laura Hitchcock

Don't read the newspapers. Be the news.� Tommy I'd

rather predict the weather three months in advance,

my sweet girl, than try to tell you one thing about

the future of the dullest heart. Dad

- "I made a

decision that in the first half of my playwriting

life, I would write about my problems as a man. In

the second half, I would turn towards society," John

Patrick Shanley told me in a 2005 interview. This

play, written in 1985, addresses the bewildering

passions of a very young couple. As usual, Shanley

makes magic with language. He juggles metaphors like

balls in the air, but each word is sharply chosen.

If some of the monologues seem to have too many

metaphors, that, too, is part of the excessiveness

of a young couple's quest and an artists's

self-protective fury. The play opens in the basement

apartment of Tommy (Jeffrey Stubblefield) who is

visited by Donna (Amanda Tepe), the girlfriend he's

jilted and whose teen-age sister he's "porking" (a

synonym for sex that's new to me. )Tommy and Donna

still love each other passionately but helplessly

because their fear and rage have brought them to a

stalemate.

A self-portrait

Tommy has nailed to his wall sends Donna on a visit

to her Dad (Eddie Jones), a painter for whom she's

had a lifelong animosity because of his treatment of

her late mother. She's afraid she's repeating her

mother's pattern, that she "could be in the middle

of somebody else's life." She learns her mother was

the love of Dad's life and, because of the intensity

of that passion, he had to create an outside space

where he could work. "Otherwise, she woulda taken me

over all the way," he confesses miserably. "I hid

part a me from her to save somethin' cause I was

scared." Now, he concludes, "what I saved wasn't

worth a god damn thing." Donna persuades Dad to talk

to Tommy and the final confrontation is summarized

by Dad's answer to Donna's question. "You went for

guys like me and him cause that's what you like an

who you are. And what you hate and makes you crazy

is that it's a mirror and what the mirror tells

you." It takes a mesmerizing cast to convincingly

capture this fascinating blend of philosophy and

aphorism below shouting level. Eddie Jones conveys a

cherubic slyness that conveys a decadent

consolation.

Amanda Tepe begins with a mannered tough girl

swagger that distracts from the genuine pain and

rage she mines from her character but by the second

act, playing against Jones with whom she has a

bonding charisma, the chip falls off her shoulder.

Jeffrey Stubblefield projects Tommy's fear and

passion with intense credibility. Director Anita

Khanzadian keeps the tension high and subtle.

Production values are first rate. Victoria Profitt's

set has a painted floor and shaded walls which gain

texture through Carol Doehring's exquisite lighting

design. Steve Hull's sound design compositions

alternate from drums to a grumbling score that seems

to come, in Shanley's words, "from the place under

that place, where men and women can meet and talk,

if you know what I mean. And it's way down. And it's

dark. And it's old as the motherfuckin' stars.

|

|

The Dreamer Examines His Pillow

What do you get if you cross an Italian and an

Irishman? If you are lucky you get the playwright

John Patrick Shanley. Shanley is a writer of great

consequence, eloquence, and a searching passion who

makes the observer examine his or her reason for

living, He doesn't let you off of the search for

answers for a minute. For Shanley, the essential

struggle to discover and moreover, accept who you

are is uppermost. I am sad to say that my only

exposure to Shanley was seeing his romantic comedies

ITALIAN AMERICAN RECONCILIATION, the Academy

Award-winning movie MOONSTRUCK, and his recent play

DOUBT in which he wonders how we can ever be sure of

anything. In his early play THE DREAMER EXAMINES HIS

PILLOW he has the Dad say "the individual life is a

dream" and he cautions his daughter to really listen

to someone when they talk, even if what they say

doesn't make sense, because they are revealing the

dream of his life as he experiences it. Critics have

struggled to understand the "meaning" of this

marvelous play with its expressionistic surreal

monologues. I think that really misses the point.

The play, the monologues, the passionate exchanges

are what the play is about. All the characters in

this play speak from their guts at all times. What a

challenge for the director and the actors who may

not be used to this kind of honesty or passionate

examination of the themes of love, sex, parenting

and how these are intricately intertwined. The

current production of THE DREAMER EXAMINES HIS

PILLOW is a triumph.

Bravo to the

director Anita Khanzadian and her amazing actors,

her husband the veteran Eddie Jones, the incredible

and unstoppable Amanda Tepe, and the clueless

dreamer played by Jeffrey Stubblefield. They

surrendered themselves to this material and the

result is an exciting, literate (without being

intellectual) and wonderfully satisfying evening of

theatre. I felt like I was back in ancient Greece

where the purpose of their plays was to put on the

stage stories, passions, and moral complexities for

all to see from the relative safety of their seats.

The design team of the talented Victoria Profitt

(sets), Steve Hull (sound design and composer) and

Gelareh Khalioun (costumes) create a perfect world

for the play. Proffit's sets evoke the

expressionistic, often messy landscape of modern

art. Hull's compositions are almost primitive in

their sound with rhythmic drumbeats (heart beats or

jungle drums) punctuating given moments. Khalioun's

costumes provide a stark palette for the play of

black, white. and red. In his author's note Shanley

states: in the third scene of this play, Dad Says,

"the individual life is a dream. For me personally

this is a most moving idea. It frees me from my fear

of death. It puts my ego where it belongs, in a

place of secondary importance. It binds me to the

human race, and binds the race itself to the atoms

in the stars, - This I think says it all. McCADDEN

PLACE THEATRE � 1157 McCadden Place in Hollywood.

Through Oct. 14th 818 765 8732.

|

Beggars in the House of Plenty

By Joel Hirschhorn

Unlike his Pulitzer Prize-winning "Doubt" and his

Oscar-winning "Moonstruck," playwright John Patrick

Shanley's "Beggars" doesn't have clean, linear

clarity. It comes at you in non sequiturs, mixes

screwball comedy with grim drama, and shifts between

reality and illusion. The ingredients don't always

work, especially some heavy-handed climactic

confrontations. When they do, it's because of

Shanley's original, zany wit, an exceptionally fine

portrayal by Johnny Clark and excellent acting all

around. Clark is 5-year-old Johnny as the story

starts, son of cold Noreen (Annie Abbott) and cruel

Pop (Eddie Jones), a butcher who relishes working in

a slaughterhouse and arrives onstage in a

blood-soaked apron. The apron signals Pop's violent

tendencies, and when Johnny's older brother Joey

(Jeffrey Stubblefield) returns home from Vietnam,

Pop excoriates him for not completing high school,

emphasizing that he regards Joey's dropout status as

a heinous, inexcusable crime. Johnny's sister Sheila

(Kimberly-Rose Wolter) is about to be married,

waving aside warnings from relative and nun Sister

Mary Kate (Amanda Carlin) that marrying a Polish

Catholic can only bring grief. Wolter is appealing

as she ecstatically contemplates her wedding ("I'm

the center of everything!"), and Carlin's boisterous

delivery makes the most of funny lines.

Director Anita Khanzadian succeeds in extracting

character nuances from this portion of the story,

but the plot dawdles, leaving spectators unsure of

what the play is about and where it's going.

Everything kicks in when Johnny (now a teenager) and

Joey have a scene that exposes every facet of their

troubled relationship. Johnny admits he can't stop

lying, setting fires and smashing windows, and Joey

taunts and terrorizes him, then says, "Johnny, I

love you," a moment that suddenly, unexpectedly,

proves deeply moving. Johnny's answering admission

to Joey, "You're my hero," carries the same

emotional weight, before mutual resentment pries

them apart again. Clark illuminates Johnny's soul

and makes clear, through the quagmire of unresolved

conflicts, that Johnny is a survivor. Joey, for all

his swagger and cockiness, is the one mortally

damaged, and Stubblefield conveys that torment

superlatively when he says to Johnny, "You think I'm

not going to make it," and suffers as his father

gives Johnny a ring, ignoring Joey's needs and

feelings. Abbott rises to the occasion when she has

a good line. After Johnny's plea, "Tell me you love

me," she responds, "It won't sound believable," a

derisive dismissal that has the bruising ring of

truth. Otherwise, her mother character is the least

interesting, filled with self-involved prattle that

pales when compared with the other principals.

As the ruthless, raging butcher-father, Eddie Jones

is pure animal, and helmer Khanzadian allows him the

lashing leeway he needs. Beefy, brutal, he reduces

Joey to "a whipped dog in a corner." He tells

Johnny, "I hit you, the same as him -- he fell

down," fully justifying Johnny's remark, "I'll never

think of you without being shocked by your

lovelessness." Inevitably, a statement emerges, "We

could have loved each other -- it was there for all

of us," but this father-son connection is so ugly

and unbalanced that a neat psychological wrap-up

isn't convincing, and it's impossible to accept that

Johnny retains any residual affection for this

monster.

Most of Shanley's tart observations avoid such easy

sentiment, and what sticks painfully in mind is the

wreckage of a family -- a destroyed, broken Joey and

the sad sight of Johnny facing the audience, knowing

even as he reaches manhood that too much damage has

been done for him to ever be fully whole. Sets, John

G. Williams; costumes, Gelareh Khalioun; lighting,

Carol Doehring; original music and sound, Brian

Benison; production stage manager, Carole Ursetti.

Opened, reviewed Sept. 10, 2005; runs through Oct.

9. Running time: 2 hours.

|

|

BIO |

RESUME |

ARCHIVES |

|